What are Gray Scale Values in CT?

Imagine you’re coloring a picture with only shades of gray, from pure black to brilliant white.

- The gray scale value (or sometimes just called the CT number) is simply a number that tells the computer exactly what shade of gray to use for every tiny little spot (called a pixel) in the picture.

- This number isn’t just random! It’s a measurement of how much the X-ray beam was blocked (or attenuated) by the part of the body it passed through.

- Very Dense Things like bone block a lot of X-rays. They get a high number and show up as bright white on the screen.

- Less Dense Things like air block almost nothing. They get a very low number and show up as dark black (like the air in your lungs).

- Everything Else (like water, muscle, and fat) falls somewhere in between and shows up as different shades of gray.

How are they Quantified and Standardized?

To make sure these gray shade numbers mean the exact same thing no matter which CT scanner is used, doctors and scientists created a special, standardized ruler called the Hounsfield Unit (HU) scale. It’s named after Sir Godfrey Hounsfield, the inventor of the CT scanner.

This scale uses two very common and easy-to-find materials as its fixed reference points:

- Water is set to 0 HU: Pure water is the middle ground. It’s the anchor of the scale.

- Air is set to -1000 HU: Air is the least dense material and is set at the lowest end.

The Standardized Scale

The CT scanner measures how much a tissue blocks the X-ray compared to how much water blocks it. The number it calculates is the Hounsfield Unit.

| Tissue/Material | Typical Hounsfield Unit (HU) Range | Shade on Scan |

| Air (in lungs/bowel) | -1000 | Black |

| Fat | -120 to -90 | Very Dark Gray |

| Water | 0 | Medium Gray |

| Muscle / Soft Tissue | +30 to +70 | Lighter Gray |

| Blood (Clotted) | +50 to +75 | Bright Gray |

| Bone (Cortical) | +500 to +3000 | Bright White |

Why is this important?

This standardization is like a universal language! If a tumor measures 60 HU in a hospital in one country, a doctor in another country instantly knows that its density is like soft tissue and not like water (which would be near 0 HU) or bone (which would be very high), even if the monitors show slightly different shades of gray. It makes the measurements objective and reliable for diagnosis.

To see a quick visual on this physics concept, watch this video: Hounsfield Units (Where do CT numbers come from?). This video explains the physics of how Hounsfield Units are calculated, which is the standardized way CT gray scale values are quantified.

What are Gray Scale Values in CBCT?

Just like in a regular CT scan, the CBCT image is made up of millions of tiny 3D boxes called voxels. Each voxel gets a Grayscale Value (GV), also known as a Voxel Value, that represents the amount of X-ray beam that was blocked by the tissue inside that box.

- High GV (Bright White): This means the tissue blocked a lot of X-rays (like tooth enamel or dense bone).

- Low GV (Dark Black): This means the tissue blocked very few X-rays (like air).

- In-Between GV (Shades of Gray): This is for everything else, like muscles and soft tissue.

How are CBCT Gray Scale Values Quantified?

The CBCT machine quantifies these values by measuring the X-ray attenuation (blocking) through the patient’s head and using a special computer process called a reconstruction algorithm (often the Feldkamp algorithm) to assign a numerical value to each voxel.

However, here’s the big difference from a regular CT scan:

- Cone-Shaped Beam: CBCT uses a cone-shaped X-ray beam instead of the thin fan-beam used in traditional CT.

- Increased Scatter: This cone beam shape leads to much more scattered X-ray radiation bouncing around inside the patient. Scattered radiation “fogs up” the picture and makes the raw density measurement less accurate and reliable.

- Different Goal: CBCT is primarily designed to maximize the detail (spatial resolution) of small, dense structures (like tooth roots), not necessarily to measure absolute tissue density.

Because of the scattered radiation and different geometry, the numbers that come out of the CBCT (the Grayscale Values) are not as precise or stable as the ones from a medical CT scanner.

Are CBCT Gray Scale Values Standardized (like Hounsfield Units)?

The short answer is No, they are not standardized like the Hounsfield Units (HU) in medical CT.

The Big Problem: Lack of Standardization

The Hounsfield Unit scale is a universal ruler where the density of pure water is always 0 HU and air is always -1000 HU.

- CBCT Grayscale Values (GVs) do not reliably equal Hounsfield Units (HUs).

- They can vary wildly between different CBCT models, or even on the same machine if you change the settings (like the exposure time or the size of the area being scanned).

What Does This Mean for the Doctor?

- Not for Soft Tissue: A regular CT can easily tell the difference between a simple cyst (near 0 HU like water) and a solid tumor (around +50 HU like soft tissue). Because CBCT values are unstable, it is not reliable for accurately distinguishing subtle differences in soft tissues.

- Relative vs. Absolute: In CBCT, we use the GVs to see relative differences (i.e., this part of the bone is clearly brighter than that part), but we cannot rely on the absolute number to mean the same thing every time (i.e., we can’t reliably say this area is 1200 GV and use that number to diagnose bone density, because 1200 GV on one machine might be 700 GV on another).

Some companies and researchers have tried to create conversion formulas to get “pseudo-Hounsfield Units” from CBCT GVs, and they often show a strong correlation (meaning the brighter the CBCT value, the higher the HU value would likely be).

However, because of the inconsistencies, these GVs are not accepted as true, standardized Hounsfield Units for general clinical use, especially not for critical radiation planning in the main body.

The Secret of CBCT’s Relative Gray Scale Values

The whole reason the dual-scan trick works in CBCT comes down to the gray scale values (GV) being relative instead of absolute.

The Conventional CT (The “Absolute Ruler”)

Imagine a medical CT machine is using a perfectly calibrated ruler (the Hounsfield Unit or HU scale) that is attached to the machine itself:

- Rule: Water is always 0 HU. Air is always -1000 HU. Bone is always high positive (e.g., 800 HU).

- When you scan a skull and a denture: The scanner looks at the density of the skull and the density of the denture, measures the X-ray blocking for both, and assigns a precise HU number to each one based on that universal ruler.

- If you remove the skull and only scan the denture: The numbers assigned to the denture’s acrylic would be exactly the same as they were before, because the machine is using the same fixed, universal rule (water is 0 HU). The denture’s GV is absolute.

The CBCT (The “Relative Best Guess”)

Now, imagine the CBCT machine is a friendly detective who has lost his universal ruler. He can’t perfectly measure absolute density, but he’s really good at comparing things within the picture he’s currently taking.

- CBCT’s Problem: The cone-beam shape causes lots of scattered X-rays, which confuses the machine. The resulting raw Grayscale Values (GV) are unstable and are not true Hounsfield Units.

- The Fix: Since the machine can’t reliably say, “This is 800 HU,” it just assigns GVs based on the range of densities it sees in the small area (Field of View or FOV) it is scanning. It sets the densest thing it sees as “White” (highest GV) and the least dense thing as “Black” (lowest GV), and scales everything in between.

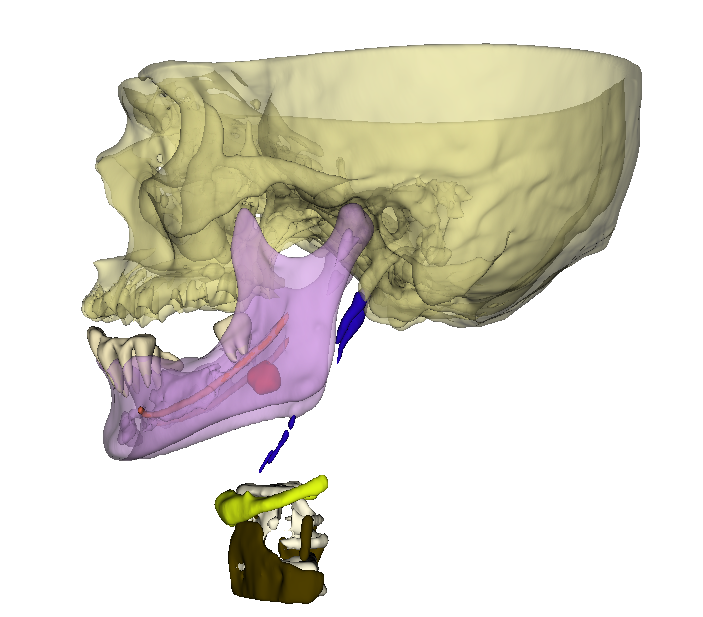

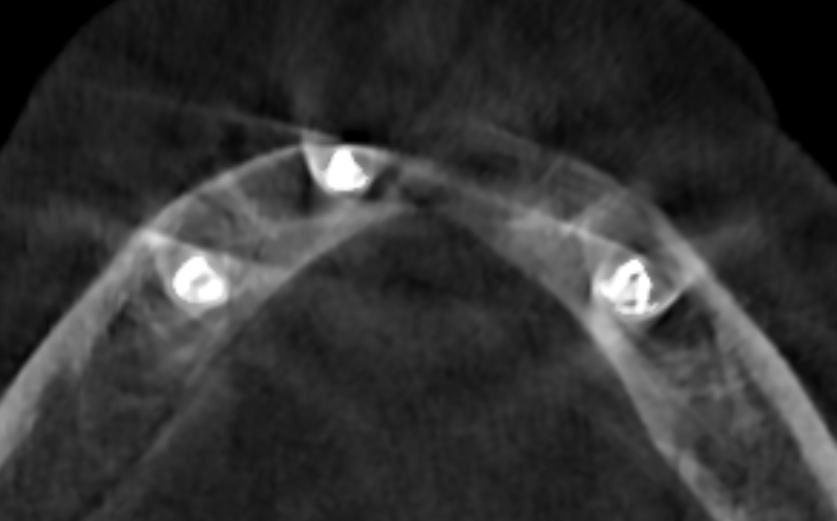

Dual Scan Protocol: The Scaling Example

The dual-scan protocol uses this relative nature of CBCT to its advantage:

Scan 1: Patient with Denture

- Content: Patient’s skull (very dense bone) + Denture (acrylic/markers).

- Scaling: The CBCT sees a huge range of densities. The skull is the densest thing, so the machine sets its GV very high. The denture material is much less dense than the bone, so it gets a lower, less dramatic GV and can be hard to see clearly against the soft tissue.

- Result: You clearly see the skull and the denture is faint or hard to distinguish.

Scan 2: Denture Only

- Content: Just the Denture (acrylic/markers) + Air + Foam block (very low density).

- Scaling: The skull is gone! The denture material is now the densest thing in the picture. Because the machine scales the GVs to the maximum density in the current field of view, the denture material is now assigned a very high GV.

- Result: The denture appears bright white and clear in the image, as if it’s bone!

The Magic (Registration)

The reason this works for the doctor is that they use tiny, high-density markers (fiducial markers) on the denture.

- They take the bright, clear denture image (Scan 2).

- They take the image of the patient with the denture and skull (Scan 1).

- They use the software to find those identical bright markers in both scans and electronically “lock” or align the two images together.

This lets the doctor superimpose the clear, detailed denture shape (from Scan 2) perfectly onto the accurate skull position (from Scan 1), giving them the best of both worlds for planning surgery.

The Algorithm Difference: Building the Picture

The different beam shapes require different “recipes” (algorithms) to reconstruct the 3D image, and this is where the Hounsfield Units (HU) are won or lost. To understand it in a better way, you should first understand how noise is produced in CT & CBCT.

The Problem: Scattered Radiation

Think of X-ray light like a bunch of tiny, fast-moving marbles.

1. Medical CT: Low Scatter

In a medical CT, the X-ray is a thin fan-beam. It’s like shooting a very thin stream of marbles through a small slice of tissue.

Result: The camera (detector) gets a very clean signal, like a clear, direct photograph. Low noise.

Most of the marbles that hit tissue either pass straight through or are absorbed.

The few marbles that bounce off (scattered radiation) often leave the detector area because the detector is only looking at that one thin slice.

2. CBCT: High Scatter

In CBCT, the X-ray is a wide cone-beam. It’s like shooting a huge volume of marbles through a large chunk of tissue all at once.

- When this big volume of X-rays hits all the atoms in that large chunk of tissue, it causes a massive number of marbles to bounce and fly off course in all directions.

- A lot of these bounced (scattered) marbles travel toward the detector, hitting it at a completely wrong spot, long after they were meant to be absorbed or passed straight through.

- The Detector’s Confusion: The detector records the scattered radiation as if it were original, useful X-ray information. It can’t tell the difference between a direct, clean X-ray and a bouncy, scattered X-ray.

This false, random information recorded by the detector is what we call noise.

How the Noise Affects the Grayscale Values

The presence of high scatter radiation directly impacts the accuracy of the Grayscale Values (GV) in two main ways:

A. Beam Hardening Artifacts

When an X-ray beam passes through dense material (like bone), the lower-energy X-rays get absorbed first. This leaves only the higher-energy X-rays to pass through, making the beam “harder.”

- In CT: The slice-by-slice method minimizes this effect.

- In CBCT: Because the entire wide beam passes through large, complex volumes of bone (like the full mandible or maxilla) simultaneously, the beam hardening effect is severe.

- The Resulting Noise: This causes streaks and dark bands to appear near dense metal or bone, distorting the GVs and making it difficult to accurately assess the tissue density in that region.

B. Decreased Contrast-to-Noise Ratio (CNR)

Contrast is how clearly you can tell two different tissues apart (e.g., a dark tumor next to gray muscle).

- Noise is random, unwanted variations in the brightness.

- The Problem: The huge amount of scatter in CBCT increases the noise level dramatically. When the noise level goes up, it becomes much harder to tell the difference between two similar gray shades.

- The Resulting Noise: Tissues with subtle density differences, like soft tissues (muscles, glands, nerves), blend together. This is why CBCT is poor at soft tissue contrast and its GVs are considered unreliable for non-bony structures.

Medical CT Algorithm: Filtered Back-Projection (FBP)

The FBP algorithm in medical CT is designed to perfectly calculate the linear attenuation coefficient μ of each tiny spot. Since the fan beam produces very little scatter, the math is very clean. The result is a number that is directly and absolutely related to the physical density of the tissue.

HU = ((μtissue- μwater)/ μwater)*1000

This formula ensures water always equals 0 HU—a standardized, absolute number.

CBCT Algorithm: Feldkamp-Davis-Kress (FDK)

The most common CBCT algorithm is called FDK (Feldkamp-Davis-Kress). While FDK is fast and computationally simple, it is essentially an approximation of the standard FBP algorithm, designed to work with the cone-shaped beam.

- FDK’s Flaw: Because the FDK algorithm has to deal with the massive amount of X-ray scatter in the raw data, it cannot accurately calculate the absolute density for every point.

- The Result: The Grayscale Values (GV) it produces are not perfectly calibrated to the Hounsfield scale. They are relative to the maximum and minimum densities seen within that specific scan (as you saw with your dual-scan example).

| Feature | Medical CT (Fan Beam) | CBCT (Cone Beam) |

| Beam Shape | Thin Fan Beam (Slice by Slice) | Wide Cone Beam (Single Rotation) |

| Scatter Radiation | Low (Clean data) | High (Noisy data) |

| Primary Algorithm | Filtered Back-Projection (FBP) | Feldkamp-Davis-Kress (FDK) |

| Gray Scale Result | Absolute (Standardized HU) | Relative (Unstandardized GV) |

In simple terms: The noise from the cone beam is too much for the simpler FDK algorithm to perfectly sort out, resulting in relative gray scale values.

What’s the truth about using HU name for GV in some CBCT machines?

Yes, it is potentially wrong, or at least misleading, for CBCT software to use “HU” nomenclature for its grayscale values.

Here is the explanation for why some software does it and the important caution for oral radiologists.

1. Why CBCT Software Uses HU Nomenclature

There are two main reasons why some manufacturers label their grayscale values (GV) as Hounsfield Units (HU):

A. The Strong Correlation (The Hope)

Although the absolute number is not the same, there is a very strong linear correlation between a CBCT’s Grayscale Value (GV) and a medical CT’s true Hounsfield Unit (HU).

In simple terms: if an area of bone is twice as dense as another area according to the CBCT’s GV, it will also be about twice as dense according to the medical CT’s HU. The numbers are linked, just not identical.

- The Manufacturer’s Logic: Since the goal is often to assess bone density for implant planning, and the traditional bone density classification system (Misch Classification) uses HU, they use the HU label to help the doctor immediately relate the value to a known classification, making the transition from medical CT to CBCT easier.

B. Attempts at Calibration (The Effort)

Some software developers have tried to build in machine-specific calibration formulas. They scan a phantom (a block of material with known densities) and then use a mathematical conversion formula to turn their raw, relative GV into a pseudo-HU value that is close to the true HU.

- The Goal: To give the user a number that is “close enough” to the standardized HU to be clinically useful.

2. Why It Is Misleading (The Reality)

The key problem is that the factors that mess up the CBCT’s absolute density measurement (like scatter radiation, the size of the Field of View, and the location of the object) are dynamic. They change with every patient and every scan setting.

Therefore, the number displayed as “HU” on one CBCT machine for a piece of bone might be 800 HU, but on a different CBCT machine (or the same machine with different settings) it might be 1200 GV, even though the tissue is identical.

Because the system doesn’t have the universal water and air reference points built in for absolute stability: CBCT HU are not universally comparable, repeatable, or interchangeable.

3. Caution for Oral Radiologists

The most important advice we can give to an oral radiologist is to never rely on the absolute numerical value displayed as HU (or GV) on a CBCT scan.

Here are four specific cautions:

Caution 1: Do Not Use It for Medical Diagnostics

Never use a CBCT’s HU reading to diagnose a condition that requires precise soft tissue density differentiation (like looking for a stroke, characterizing a liver lesion, or determining the exact density of a cyst). The values are simply too unreliable for soft tissues.

Caution 2: Use a Small Field of View (FOV)

If you must measure density for bone quality assessment (e.g., prior to implant placement), always use the smallest Field of View (FOV) possible for the area of interest. Why? A smaller FOV means less tissue is irradiated, which dramatically reduces the scattered radiation and gives you a more reliable, less noisy GV. Research shows smaller FOVs produce GVs closer to true HU.

Caution 3: Focus on Relative Density

Instead of thinking, “The bone is 1000 HU,” think, “The bone at the implant site is significantly brighter (more dense) than the bone 10mm away, and the mandible is much brighter (more dense) than the maxilla.”

Use the GV/HU number as a tool for relative comparison within the same image, not as an absolute gold-standard measurement.

Caution 4: Always Calibrate (If Quantifying)

If you are involved in research or need quantitative measurements, you must calibrate the specific CBCT machine you are using with a phantom of known densities before the patient is scanned. This allows you to generate a machine-specific formula to truly convert the relative GV to a more accurate, absolute pseudo-HU.

Conclusion: Absolute vs. Relative Density

The key takeaway from our guide on grayscale values in CT and CBCT lies in the distinction between absolute and relative density measurements.

Conventional Medical CT uses a thin fan-beam and the Hounsfield Unit (HU) scale, which is the gold standard for tissue density. This system is standardized worldwide, meaning a reading of 0 HU is always pure water, regardless of the scanner or settings. This allows us to precisely differentiate subtle soft tissues and make reliable medical diagnoses based on absolute numbers.

In contrast, Cone-Beam CT (CBCT) uses a wide cone-beam that causes more scattered radiation. This results in Grayscale Values (GV) that are relative to the materials scanned and the machine’s specific settings. While CBCT provides phenomenal spatial resolution (detail) for hard tissues like bone and teeth, it lacks the stable, absolute density accuracy of medical CT.

Therefore, oral radiologists must be cautious when software displays “HU” values, recognizing them as approximations useful for relative comparisons of bone quality within a single scan, but not as reliable for characterizing soft tissues or for comparison across different machines. Understanding this fundamental difference between absolute (CT) and relative (CBCT) grayscale quantification is essential for accurate diagnosis and treatment planning.

FAQs

What is a Grayscale Value (GV) or CT Number?

The Grayscale Value (or CT Number) is simply a numerical assignment that tells a scanning computer what shade of gray (from black to white) to assign to a tiny point (pixel or voxel) in the image. This number measures how much a specific tissue blocked the X-ray beam.

What are Hounsfield Units (HU) and why are they important?

Hounsfield Units (HU) are the standardized, absolute grayscale values used exclusively in Medical CT. They are the universal ruler for density because the scale is fixed: Water is always 0 HU and Air is always -1000 HU. This standardization allows doctors to accurately and reliably measure and characterize all soft and hard tissues anywhere in the world.

Why do CBCT machines use different Grayscale Values (GV)?

CBCT uses a wide cone-shaped X-ray beam that creates a high amount of scattered radiation (X-ray “noise”). This scatter interferes with the density measurement, preventing the system from achieving the stability needed to apply the fixed Hounsfield Unit scale. CBCT values are primarily relative.

What does “Relative Grayscale Value” mean in CBCT?

It means the numerical value assigned to a tissue (like bone) is scaled based on the highest and lowest densities present in that specific scan. The number for a piece of bone might be 800 GV in one scan, but 1200 GV in another, even if the bone is identical, because the scanner scaled the numbers differently for each scan’s unique range of densities.

Why does the Dual-Scan Protocol work with CBCT but not Medical CT?

The dual-scan protocol relies on the relative nature of CBCT. When you scan only the denture, it becomes the densest object in the field of view and is automatically assigned a high, bright GV. Since Medical CT uses absolute HU (where the denture’s density is a fixed number), scanning the denture alone doesn’t change its numerical value, making the technique less practical for alignment.

Is it wrong for CBCT software to use the “HU” label?

It is misleading. While the CBCT Grayscale Values (GV) are highly correlated with true HU, they are not standardized or accurate enough to be used interchangeably with medical CT’s Hounsfield Units. Oral radiologists should treat these numbers as a guide for relative comparison of bone density, not as a precise, absolute measurement.

- Steiner’s Analysis – Free online Cephalometry - November 23, 2025

- A Complete guide to Grayscale values in CT & CBCT - November 15, 2025

- Struggling to get your old PC to run new Radiology software smoothly? Here’s a trick with SSD that might save you. - November 14, 2025